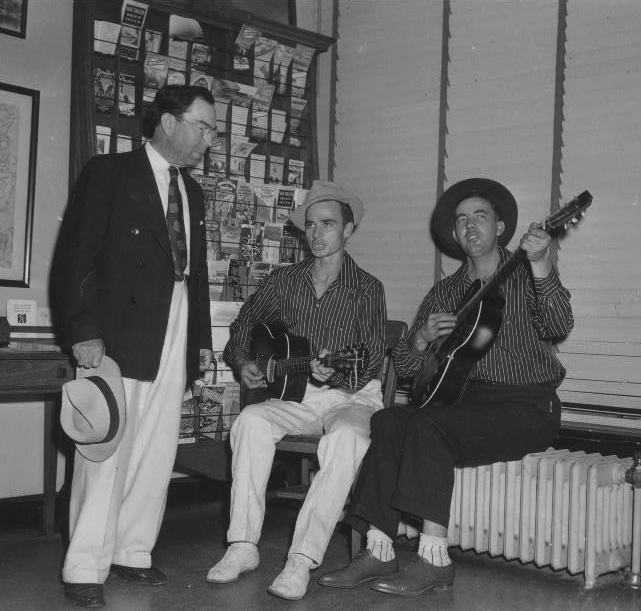

Bascom Lamar Lunsford, born in 1882 in Madison County, was a fruit tree salesman, teacher, and lawyer, who is celebrated for his lifelong devotion to Appalachian music and dance. Lunsford learned to play the banjo and fiddle, and collected songs and tunes. He began his repertoire during the folk revival of the 1920s. Over the years, he recorded over 3,000 songs for the Library of Congress and the Columbia University Library. He performed at the White House for the King and Queen of Great Britain, and wrote the well-known “Old Mountain Dew”, which he sold for money for a bus ticket. In 1928, he organized the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival that continues in Asheville to the present. Mars Hill College maintains a museum dedicated to him.

One voice seized me more than the rest. Over a simply picked banjo, the voice sang mournfully about a mole in the ground. Elsewhere, the same voice preached, over that same simple banjo, about dry bones. Like so many folk tunes, these told strange, elliptical stories, dense with images, exploding with emotion.

~The recollections of folklorist, Chris King, recounting the first time he heard Bascom Lamar Lunsford.

Multimedia:

Below is the Digital Heritage Moment as broadcast on the radio:

[audio:http://dh.wcu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/Lunsford60Mx.mp3|titles=Lunsford60Mx]

Bascom lamar lunsford

Essay by Timothy N. Osment, History M.A., WCU 2008

Bascom Lamar Lunsford was born in 1882, in the beautiful rolling hills of Madison County just north of Asheville, North Carolina. His father, a teacher, bought Bascom and his brother a fiddle and a banjo at a young age. Inspired by a mother who softly sang mountain ballads and religious songs around the house, Bascom began a love affair with old-timey music that would last throughout his lifetime. He became recognized locally by playing at dances, weddings, and other social occasions.

Lunsford was incredibly prolific as a song-writer/collector, a recorder, and a performer. Some of the most famous tunes he popularized were “Jesse James,” “I Wish I Were a Mole in the Ground,” and “Mountain Dew.” His first sessions were in 1922 when he recorded 32 tunes on wax cylinders for a song collector. He went on to record commercially for the General Phonograph Company. Lunsford recorded many of the thousands of songs he learned for the Archive of American Music at the Library of Congress. One of his more noted performances was at the White House in 1939 when he delighted the visiting King and Queen of Great Britain with several mountain ballads.

Because of his interest in preservation, Lunsford also enjoyed children’s ballads, slave spirituals, and parlor songs. He avoided music with racy or controversial lyrics. Lunsford played a unique style of banjo featuring an up-stroke that sounded similar to the traditional clawhammer style of mountain picking. He also played a “mandoline,” an instrument with a mandolin body and a 5-string banjo neck. His trademark was his delivery, featuring a gravelly, tight voice combined with high notes. Listening to similarities found in early Bob Dylan recordings, music fans and historians quickly recognize the sweeping influence Lunsford had on generations of performers.

Lunsford did not limit his talents to music. In fact, during his life he pursued many professional avenues, making his story even that much more interesting. He was a fruit tree salesman and traveled the region with a Cherokee beekeeper. He exchanged lyrics and tunes with would-be customers. During World War I, he moonlighted as an agent chasing draft evaders. In 1909, after finishing at Rutherford College he became a teacher. Later he would study law at Trinity College [now Duke University]. He passed the bar in 1913 and became a licensed solicitor — even working for several years with the NC Legislature.

Throughout it all, he never relinquished his love of music and his Appalachian roots. In 1927, the city of Asheville was planning a Rhododendron Festival to encourage tourism. They asked Lunsford to invite local musician and dancers to what would eventually become the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival. Still held annually, it is recognized as the first event to be labeled a “folk festival.” Lunsford performed there for almost 40 years, until he suffered a stroke in 1965.

Today, Lunsford is remembered as a one of the true musical treasures to emerge out of the Southern Appalachians. His legacy is preserved in the National Archives and in films, recordings, and festivals. Mars Hill College in Madison County houses the Bascom Lamar Lunsford Scrapbook and Ballad Collection in its Appalachian Room. Lunsford’s instruments are also on display at the college, and the school hosts an annual festival named for him where performers grace the Lunsford Stage.

Bascom Lamar Lunsford died in 1972. However, his life and music live still safely embraced as a cherished and valuable part of our mountain heritage.

For more information

- “Hank Williams: So Lonesome; Minstrel of the Appalachians: The Story of Bascom Lamar Lunsford; Old-Time Kentucky Fiddle Tunes.”

,Steve Goodson, The Southern Quarterly, Summer 2003. - Minstrel of the Appalachians: The Story of Bascom Lamar Lunsford, Loyal Jones and John Forbes, 1984.

- It Used To Be: The Memoirs of Bascom Lamar Lunsford, Bascom Lamar Lunsford and Mildred Frances Thomas, 1975.

- “Minstrel of the Appalachians: The Story of Bascom Lamar Lunsford.” Mary Larson, The Oral History Review, Summer/Fall 2003.

- Minstrel of the Appalachians: An Interpretative Biography of Bascom Lamar Lunsford, John Angus McLeod, 1970.

- Ballad of a Mountain Man: The Story of Bascom Lamar Lunsford, Donn Rogosin, video, 1990