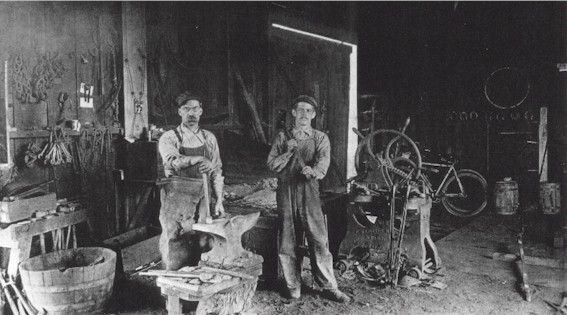

Long before Western North Carolina was celebrated by visitors for its majestic Blue Ridge Parkway views; even before it was recognized by the ailing for its beneficial climate and therapeutic mountain air, our region was famous for something else: its seemingly-infinite amounts of mineral wealth. Blacksmithing was an essential skill and also became a highly-valued art.

Multimedia:

Below is the Digital Heritage Moment as broadcast on the radio:

[audio:http://dh.wcu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/Blacksmith60MX.mp3|titles=Blacksmith60MX]

Blacksmithing essay

Essay by Timothy N. Osment, History M.A., WCU 2008

Initially, early settlers utilized iron deposits found in bogs along North Carolina’s coast. As exploration expanded, large deposits of iron ore were discovered in the mountains several hundred miles to the west. In fact, by the early 1800s, the range we now refer to as the Great Smoky Mountains was known throughout the growing United States as the Great Iron Mountains.

The combination of abundant iron ore and vast tracts of timber in close proximity to one another gave our region a natural ability to produce a large variety of iron products. Where there is little coal, such as in western North Carolina, charcoal is alternatively used to smelt iron ore. Huge quantities of wood were required to power the iron-making process. One manufacturer suggested that to keep a large iron furnace in continuous and sustained operation for one year, seven to ten thousand acres of mountain timberland were required to supply the needed fuel–and, notably, there were hundreds of these furnaces located in the region during the early 1800s. Predictably, this rapid and extensive removal of iron ore and forestland had a dramatic effect on the environment, leaving the scars of mining along with barren, treeless landscapes.

“[The Cherokee] have acquired a knowledge of most of the mechanic arts known by their white

While the Cherokee and other Indian tribes had forged decorative works out of silver and gold for many years, they had not developed the ability to process iron. That skill arrived with European settlers. Soon every pioneer community had its own blacksmith. Forging iron into tools was a necessity as early colonists carved their existence out of an untamed frontier. Additionally, the ability to make weapons out of iron gave settlers a technological advantage over frequently hostile native populations. It is not an exaggeration to suggest that iron tools and weapons made mere survival possible for early European settlers.

Blacksmithing was essential and the trade touched virtually every aspect of pioneer life. Families that settled in distant, remote corners of the mountains were often miles from the nearest blacksmith. Out of necessity, these remote, independent farmers learned the trade themselves often using their own anvil and forge to make and repair tools and household items. Objects produced included: shoes for mules, oxen and horses; farming tools like

Blacksmithing was essential and the trade touched virtually every aspect of pioneer life. Families that settled in distant, remote corners of the mountains were often miles from the nearest blacksmith. Out of necessity, these remote, independent farmers learned the trade themselves often using their own anvil and forge to make and repair tools and household items. Objects produced included: shoes for mules, oxen and horses; farming tools like

Early in the twentieth century as more modern and efficient methods of metallurgy were developed,

Today it is common to see traditional blacksmiths demonstrating their talents at fairs, festivals, and craft shows throughout the region.

for more information

- By Hammer and Hand: Blacksmithing in Western North Carolina, David Brewin and Tyler Blethen, 1992.

- Irons in the Fire, Tyler Blethen, ed., 1992.

- Where There Are Mountains, Donald E. Davis, 2000.

- The Village Blacksmith, Kenneth H. Dunshee, 1977.

- The Art of Blacksmithing, Alex W. Bealer, 1976.

- Blacksmithing in Western North Carolina: a Folklore and History Project at an Appalachian Museum, John Allen Davidson, Jr., 1992.