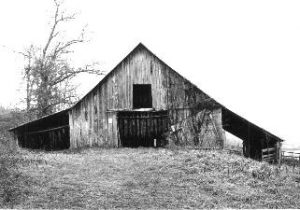

For over 100 years burley tobacco has been an important cash crop in western North Carolina as well as in other areas of Appalachia. The large, weather-beaten, rough-timbered tobacco barns that dot the landscape are a familiar sight. In many mountain families, several generations worked side by side on small farms – planting, harvesting, and curing burley tobacco. However, like many other agriculture commodities, tobacco production is changing. In fact, the combination of market evolution and new legislation is threatening the survival of the burley tobacco industry in our region.

Multimedia:

Burley tobacco essay

Production

Three kinds of tobacco are used in cigarette production: bright, burley, and oriental (also called Turkish) – with bright and burley being the two varieties grown in the United States. By far, bright is the most common. North Carolina growers produce about 348 million pounds of flue-cured bright tobacco and about 10 million pounds of naturally-cured burley.

Three kinds of tobacco are used in cigarette production: bright, burley, and oriental (also called Turkish) – with bright and burley being the two varieties grown in the United States. By far, bright is the most common. North Carolina growers produce about 348 million pounds of flue-cured bright tobacco and about 10 million pounds of naturally-cured burley.

The process of growing and selling burley is similar to that of bright, but there are significant differences in the way it is harvested and cured. With burley, the entire stalk is cut and left stacked teepee-style in the fields. The stacks are then collected and allowed to air-cure in large open barns with natural air-flow. In fact, the technical term for burley is “air cured.” After one to two months of curing, burley leaves will turn

While bright tobacco was king in the

Tobacco Quotas

In 1938 the United States government, responding to the Great Depression, implemented a price control mechanism on tobacco called “quotas.” This system was intended to ensure that the industry remained viable and profitable to farmers by limiting production and providing price supports. Over the years, the larger, richer landowners purchased quotas from smaller farmers. Frequently, these large growers would “sharecrop” the production rights back to smaller farmers, in effect recreating the

Future of Tobacco Farming

Many experts believe the big farms will survive in a market environment. Since supply restrictions have been eliminated, some may even grow in size. However, smaller farms are already beginning to disappear. The largest producer of burley in North Carolina, Madison County, had over 1,200 tobacco farmers in 1993. Since the quota system was eliminated, that number has dwindled to less than 700. Coupled with a declining demand for cigarettes and pressure from Turkish and Brazilian imports, the future of the industry is uncertain.

Agricultural economists are recommending that tobacco farmers, especially

This essay was based on information provided by Phillip Morris USA, the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, the Asheville Citizen-Times, and Duke and N.C. State Universities.

for more information

- “Tobacco Farming in the Age of the Surgeon General’s Warning: The Cultural Ecology and Structuration of Burley Tobacco Production in Madison County, North Carolina,” by Catherine Algeo, 1998.

- Characteristics of Burley Tobacco Farms, by Tom Capehart, 1991.

- Seeds of Wealth: Four Plants That Made Men Rich, by Henry Hobhouse, 2003.

- Mister Golden Leaf Himself, by the North Carolina Farm Bureau Federation, 1994.- This video describes the similarities and differences between the two types of tobacco grown in North Carolina and how the tobacco industry benefits North Carolina’s economy

- Tobacco Culture: Farming Kentucky’s Burley Belt, by John van Willigen and Susan C. Eastwood,1998.