Appalachian religious belief and expression were deeply influenced by the camp-meeting movement that swept the South in the early 19th century. These large outdoor revival meetings, lasting several days, were a central feature of the Great Awakening and ideally suited to a frontier region with few established churches and fewer ministers. Deeply emotional and evangelical, camp meetings are credited with moral reform and the rapid growth of church membership until, by the 1840s, the established meeting-houses of Methodists and Baptists began to replace them. In the late 19th century, the movement reappeared in Appalachia as Holiness groups in the Methodist Church adopted camp-meetings and renewed the emotional spirituality of the Great Awakening in new Holiness and Pentecostal churches across the mountain region.

Religion has been a steering influence in the history of not only the Appalachian region but the United States itself. Like other immigrants, early European settlers brought religion with them to the New World. Established European religions were recast to accommodate their new environments. In the early 1700s, New England Anglicans, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists rose in a Great Awakening calling their followers to adhere to stricter and more involved guidelines. Several ministers took that inspiration south to Virginia and North Carolina where Baptists and Methodists grew to eventually outnumber other denominations.

The south had few church facilities and even fewer ordained clergy. For the vast majority of individuals and families living outside small population centers, the only religious guidance was offered by an occasional circuit preacher. These horse-mounted ministers were welcomed as they traveled through the undeveloped wilderness visiting rural people in their homes. Occasionally they would gather several families together in one location and hold impromptu church services. Despite these efforts, by the early 1800s many parts of the south, including Appalachia, still remained outside of any significant church influence. Many rural areas were virtual spiritual vacuums. This religious depression was a result of both isolation and the structural and institutional disruption caused by the American Revolution. However, some faithful interpreted this religious drought as a form of punishment from God. They felt another awakening was needed to restore the nation, and the region, to its proper position in the spiritual universe.

Occasional revivals began to be held in small communities in various Appalachian locations. Those meetings sought to reinvigorate the populace’s relationship with God, especially those that were either ignoring or had abandoned Him. Speakers urged their audiences to develop a personal accountability with God, themselves, and their communities. Traditional organized religious institutions were labeled as unnecessary and oppressive. Such revivals were trademarked by powerful, emotional preaching, and the crowds they attracted grew larger and larger.

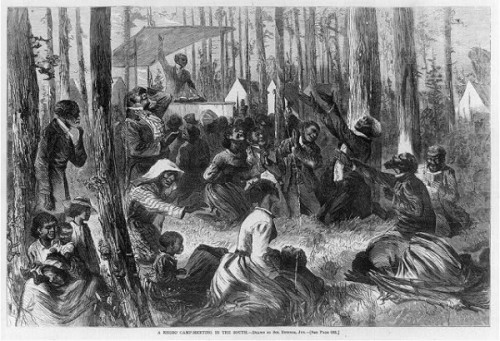

In 1798, a huge gathering in Cane Ridge, Kentucky, marked the unofficial beginning of the style of worship that became known as the Camp Meeting. There over 20,000 people–black, white, free, and bonded–joined Methodist, Presbyterian, and Baptist ministers for several days of non-stop, fiery religious celebration. Many of the prominent characteristics of the Cane Ridge meeting, such as outdoor location, intense emotionalism, and physical frenzy, became the model for future revivals.

Camp meetings were rural by nature. Scheduled so as not to interfere with the farming cycle, they were usually held within an outcropping of trees near a stream or other body of fresh water. Transportation was slow and primitive, so any meeting more than a few miles from home required that attendees stay overnight. Individuals and families planned provisions for several days and “camped’ for the length of the revival. Public orators were the celebrities of the day, and attending public speaking events was a favorite form of entertainment for rural folk who normally had infrequent outside contact during their daily routines. Camp meetings were festive, on a par with the excitement generated by county fairs and political campaigns. Poverty and isolation were common in rural Appalachia, and camp meetings provided rare opportunities for folks to get away from their hard existence and visit with friends and neighbors.

Despite the social component, religious participation and renewal dominated camp meetings. Attendees were removed from their daily responsibilities so services, though informal, could be held nonstop, from sunup to sundown–and often late into the night. Frequently, pulpits were erected in several locations throughout the vast meeting sites. Speakers from various dominations provided sermon after sermon.

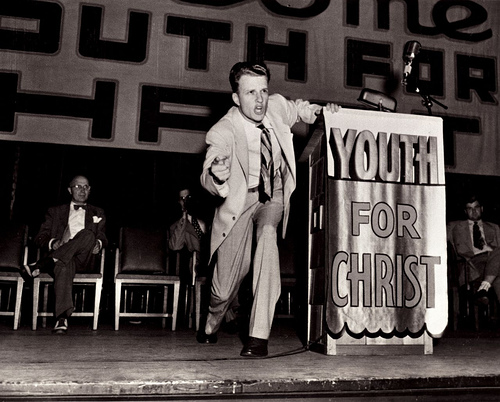

When Jonathan Edwards preached his infamous “Sinners in the Hand of an Angry God” during the First Great Awakening, he set the tone for the camp meeting sermons that followed a century later. The speakers were intensely emotional and experts at working their audiences into a feverish, religious frenzy. Abandoned was the old custom of quietly and reverently listening to a solemn, spiritual message presented by the leader of the local community church. Worship became exuberantly physical. Singing and shouting was augmented with “falling, jerking, rolling, barking, and laughing.” Preachers and congregations became “barnstormers for Christ,” “born-again devil fighters” anxious to “get their cups filled.”

Camp meetings had a huge influence on both religious practice and society. The meetings were instrumental in transforming the social landscape of Appalachia, the south, and the nation. Church memberships exploded. In the ten years after Cane Ridge, Methodist membership rolls alone doubled. Presbyterians backed away from revival participation but built hundreds of churches in small, isolated communities. Baptists capitalized on the enthusiasm generated by camp meetings and soon became the largest domination in the south, and eventually the nation.

After the devastation caused by the Civil War, religion and camp meetings helped define and heal the defeated south–especially the reeling communities in and around the Appalachians. By now Methodists and Baptists no longer required remote revivals to support their growth and outreach. Small “holiness” groups began to hold camp meetings to recapture some of the fervor lost during the War and Reconstruction years. Out of these meetings grew the evangelical Pentecostal movements. These groups abandoned the doctrinal guidelines of the large, traditional dominations and rejected “learned preaching for Spiritual-led utterance.” Uniquely Appalachian in nature, Pentecostal and Holiness churches are direct descendants of the Second Great Awakening and camp meetings and have proliferated in the region.

In the rural south, and especially in Appalachia, religion has long been a component of the region’s social fabric. Church and worship exist within rather than removed from life’s daily activities. Camp meetings were (and remain) examples of both rural, mountain interdependence and independence. As part of the region’s heritage, Camp Meetings were important building blocks in the construction of a distinct Appalachian identity.

Bibliography:

- “Camp Meeting Movement” in Encyclopedia of Appalachia Rudy Abramson and Jean Haskell, eds., 2006

- Glory, Hallelujah!: The Story of the Campmeeting Spiritual, Ellen Jane Lorenz, 1980

- And They All Sang Hallelujah: Plain-Folk Camp-Meeting Religion, 1800-1845, Dickson D. Bruce Jr., 1974

- The Great Revival, 1787-1805, John B. Boles, 1972

- Camp Meeting Entry from Wikipedia

- Johnny the Baptist.org

Contributors

- Essay by Timothy N. Osment, (Graduate Assistant in History with Tyler Blethen)

- Images researched by Rebecca Messer (HIST 341: North Carolina History with L. Scott Philyaw)

Multimedia:

Below is the Digital Heritage Moment as broadcast on the radio:

[audio:http://dh.wcu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/CampMeet60Mx.mp3|titles=CampMeet60Mx]