Image Courtesy of The Great Smoky Mountains National Park Archives

Essay by Timothy N. Osment

Essay by Timothy N. Osment

History, M.A.

WCU 2008

“From Asheville to the Tennessee line, the Southern Railway follow the tortuous windings of the French Broad River, crossing it from bank to bank several times.” ~From “With Pen and Camera thro’ the Land of the Sky, 1904.”

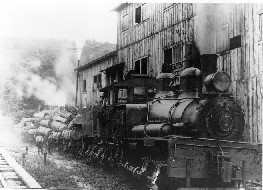

Early in the 19th century railroads were being built throughout the expanding United States. Western North Carolina was growing as well. Asheville, a crossroads for agriculture, was also emerging as a magnet for tourists seeking the healing climate, loggers looking to harvest timber, and miners interested in the large deposits of minerals.

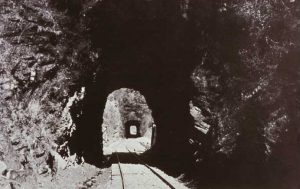

Easy access was a necessity for all of these groups, and railroad expansion offered the solution. Financial backing and the rugged terrain were immediate challenges. But the Civil War, which devastated families, businesses, communities, and commercial growth, blocked railroads for over a decade.Until the 1870s, railway routes to western North Carolina ended at the steep mountainside at Old Fort. There goods and passengers were required to transfer to stage coaches. Finally, in March 1879, after several years of difficult construction and great expense, the railroad finally entered Buncombe County through the Swannanoa Tunnel. Less than twenty years after the end of the Civil War, the Eastern Continental Divide was conquered. On October 3, 1880, the Western North Carolina Railroad made its first scheduled arrival at Biltmore. Trains brought money, power, and a taste of affluence to Western North Carolina.

The Murphy branch of the WNC RR made it to Pigeon River (present-day Canton) in January 1882 and Waynesville later the same year. Now Balsam Mountain challenged the railroad’s trek west. Abandoning plans to tunnel through the mountain, engineers laid the tracks along a dangerous and difficult grade up and over Balsam. At 3100 feet, Balsam Gap became the highest railroad pass east of the Rockies. From there the WNC RR dropped into Dillsboro and proceeded to Bryson City and Andrews, finally reaching Murphy in 1891. Murphy celebrated by laying the cornerstone of its new courthouse on the same day the railroad made its first scheduled stop in the town.

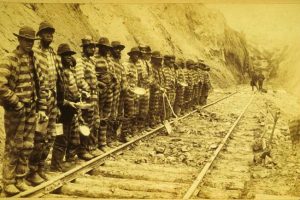

One of the saddest episodes in constructing the WNC RR occurred when workers were constructing the 863-foot Cowee Tunnel, just west of Dillsboro. At the time, prison chain-gangs were being exploited as a cheap source of labor. One morning, crossing the Tuckasegee River to the tunnel, a boat carrying iron-shackled convicts capsized. Bound in death as in life, 19 inmates drowned. With sad irony, they were buried in unmarked graves on a hill overlooking the tunnel.

One of the saddest episodes in constructing the WNC RR occurred when workers were constructing the 863-foot Cowee Tunnel, just west of Dillsboro. At the time, prison chain-gangs were being exploited as a cheap source of labor. One morning, crossing the Tuckasegee River to the tunnel, a boat carrying iron-shackled convicts capsized. Bound in death as in life, 19 inmates drowned. With sad irony, they were buried in unmarked graves on a hill overlooking the tunnel.

Take the train from Asheville to Murphy.

The WNC RR experienced its heyday in the 1940s during construction of the Fontana Dam. At the time, the temporary “Fontana Village” was the largest city west of Asheville. The increased popularity of automobile and bus travel took its toll on the railroad. Passenger service was discontinued in 1948. Freight traffic declined as resources like lumber, copper, and iron were depleted. In 1988 the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad was created in Dillsboro. The industrial focus of the rails now shifted to tourism and preservation. As a living museum steeped in history, the GSMR carries nearly 200,000 passengers annually. Today, modern day rail travelers follow the same breathtaking route once used by dignitaries, families, laborers, logs, and minerals. “Eat Taters and Wear No Clothes!” That was the nickname locals gave the East Tennessee & Western North Carolina Railroad. Another early railroad in Southern Appalachia, it ran from Johnson City, Tennessee, to Boone, North Carolina, from the late 1800s until 1950. For several rural mountain communities it was one of the few sources of contact with the outside world during the Great Depression. Respected and loved for their neighborly ways, employees of the ET & WNC were known to pick up items “in town” for those unable to make the trip–and even sometimes let locals jump on and ride for free. When questioned about their generosity they replied, “Well, we were going that way anyhow!” Before the railway was completed it was often commented that the only way to get to Boone was to be born there. The shrill whistle of the ET & WNC echoing through the mountains was a comfort to local residents and provided an additional nickname, The Tweetsie.

This essay was produced primarily from information gathered from The Great Smoky Mountains Railroad, the Archives of Appalachia at East Tennessee State University, The History of Western North Carolina by John Arthur and Jeffrey Weaver, and johnsonsdepot.com.

This essay was produced primarily from information gathered from The Great Smoky Mountains Railroad, the Archives of Appalachia at East Tennessee State University, The History of Western North Carolina by John Arthur and Jeffrey Weaver, and johnsonsdepot.com.

For more information please see:

- The Western North Carolina Railroad, 1855-1894 by William Abrams, Jr., 1976.

- Tweetsie Country: the East Tennessee and Western North Carolina Railroad by Mallory Ferrell, 1991.

- Trains, Trestles, and Tunnels: Railroads of the Southern Appalachians by Lou Harshaw, 1977.

- A History of Railroading in Western North Carolina by C. Franklin Poole, 1995.

- Reminiscences of an Old-Timer by Ross Smith, 1930.

- Railroad Crossings of the Blue Ridge: 1879-1909 by Neal Westveer, 1990.

Online Resources:

Multimedia:

Railroads in Western North Carolina Digital Heritage Moment from Digital Heritage {dot} Org on Vimeo.