For several years during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, tuberculosis was the leading cause of death in the United States. Consequently, a wide variety of treatments emerged claiming to sooth, even reverse, the disease. The most popular and widely accepted of those treatments involved placing the afflicted in an environment that boasted clean air, low humidity, cool nights, and abundant sunshine. By the late 1800s, “sanitariums” designated for TB treatment were being built in various temperate locations throughout the country. Due to its climate, Western North Carolina quickly emerged as one of the premier destinations for those suffering from tuberculosis.

Multimedia:

Sanitarium essay

Essay by Timothy N. Osment, History M.A., WCU 2008

Asheville’s Role

Records of European settlers dating to 1795 describe the healing effects of Appalachia’s natural environment. For centuries, Native Americans had designated the lands around modern-day Hot Springs as “neutral,” thus reserving the region as a sanctuary where the ill from various tribes could go to convalesce. By the mid-1800s, though travel was difficult and the area relatively isolated, doctors around the country were prescribing a beneficial relocation to Western North Carolina for TB patients. When the railroad was completed in the 1880s, the region’s largest city, Asheville, found itself host to thousands of TB sufferers. In order to accommodate the sick, grand facilities were constructed.

Records of European settlers dating to 1795 describe the healing effects of Appalachia’s natural environment. For centuries, Native Americans had designated the lands around modern-day Hot Springs as “neutral,” thus reserving the region as a sanctuary where the ill from various tribes could go to convalesce. By the mid-1800s, though travel was difficult and the area relatively isolated, doctors around the country were prescribing a beneficial relocation to Western North Carolina for TB patients. When the railroad was completed in the 1880s, the region’s largest city, Asheville, found itself host to thousands of TB sufferers. In order to accommodate the sick, grand facilities were constructed.

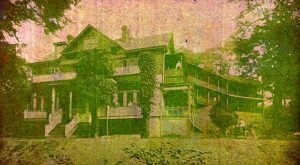

One representative structure, now an apartment house, is located in the residential

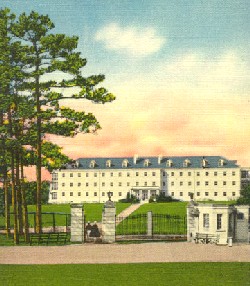

Another well-known sanitarium opened in the 1930s, a state-financed 1,000-bed facility just east of Asheville in the community of Oteen. It provided care to war veterans. Today, its impressive buildings command a majestic, eerie presence as they sit abandoned across from the modern VA hospital.

Health Concerns

From the beginning, Asheville was wary of a large influx of outsiders suffering from infectious disease. A 1912 bulletin from the local health department demanded that the sick conduct themselves so as not to become a menace to local citizens. Like many communities, Asheville passed laws prohibiting “spitting on the sidewalk,” reflecting the fear of TB transmission. Other ordinances required spittoons to be present in public venues.

From the beginning, Asheville was wary of a large influx of outsiders suffering from infectious disease. A 1912 bulletin from the local health department demanded that the sick conduct themselves so as not to become a menace to local citizens. Like many communities, Asheville passed laws prohibiting “spitting on the sidewalk,” reflecting the fear of TB transmission. Other ordinances required spittoons to be present in public venues.

Despite the purported benefits of mountain air and specialized treatment in Asheville’s sanitariums, 75% of those who entered the facilities were dead within five years. It was not until the 1940s, with the development of antibiotics like streptomycin, that treatment for TB became effective and a cure truly possible. Within a few short years, sanitarium care fell out of

Legacy

The impact of the dozens of tuberculosis sanitariums constructed in Asheville was great. Facilities originally designed to nurse the sick have been preserved and renovated into stately homes. Their rich architecture

The impact of the dozens of tuberculosis sanitariums constructed in Asheville was great. Facilities originally designed to nurse the sick have been preserved and renovated into stately homes. Their rich architecture

One influential caretaker,

Asheville is still a health

Though the link between

For more information please see:

- A Guide to the Architecture of Western North Carolina, Catherine Bishir, Michael Southern, and Jennifer Martin, 1999.

- “Asheville: The Tuberculosis Era,” North Carolina Medical Journal, Irby Stephens,1985