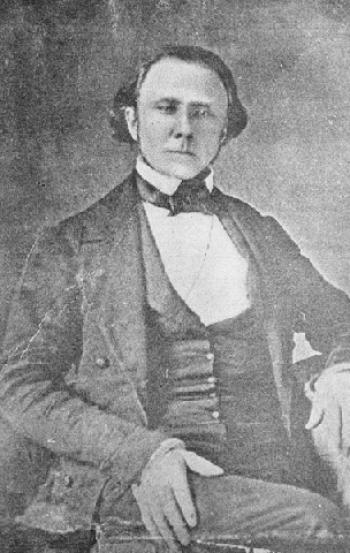

William Holland Thomas, born in Haywood Country in 1805, was befriended and adopted by the Cherokee leader, Yonaguska. Thomas’s close ties to the Cherokee promoted his success as a merchant. It is difficult to image their survival as a tribe without his tireless efforts on their behalf following their forced removal to Oklahoma. His leadership of the Thomas Legion during the Civil War is one of the great stories of that era. Tragically, his last years were burdened by a long period of mental decline before his death in 1893. Frontier merchant, Civil War soldier, state senator, Indian agent and tribal leader–few people have left a deeper mark on the history of the region than William Holland Thomas.

Few individuals have impacted western North Carolina as did native son William Thomas Holland. In fact, he was arguably the region’s most influential figure during the 19th century. He is best known for two things: his work with the Cherokee, helping them to survive in North Carolina as the Eastern Band, and his Civil War command of the Thomas Legion.

Thomas was born an orphan in Haywood County, NC, in 1905. His father drowned several months before he was born. At the age of 15, he was apprenticed to United States Congressman Felix Walker to help operate a trading post about 50 miles east of Waynesville in the heart of the Cherokee nation. There Thomas learned the culture and language of the native people and became a close friend of the Cherokee Chief, Yonaguska. Congressman Walker was not a wise businessman and eventually went broke. With no cash to pay his young employee, he instead gave Thomas a set of law books. In the early 19th century, before bar exams, an individual who could read law could practice law. Consequently in 1831, after studying the books thoroughly, Thomas was asked by his friend, Yonaguska, to become the legal representative of the Cherokee tribe. This was the formal beginning of a relationship that would not only shape the history of William Holland Thomas and the Cherokee, but of the entire region.

Thomas made his home near the modern day town of Whittier. He operated a merchant store, primarily trading with the Cherokee, but also with the growing population of European settlers pouring into the mountains. Thomas bought large tracts of land, eventually opened several additional small trading posts, and became firmly immersed in the Cherokee culture–in essence becoming a member of the clan. When the U.S. Government began removing and relocating the Cherokee to Oklahoma in 1838, Thomas negotiated a deal allowing the 60 Cherokee families residing in Quallatown the right to remain on their land. So important and integral had Thomas become to the Cherokee that one year later, in 1839, a dying Yonaguska designated Thomas his successor as Tribal Chief.

The Cherokee had no more dedicated and tireless benefactor than William Thomas. After ten years of success, both in business and in assisting the development of a Cherokee identity in an ever-expanding white man’s culture, Thomas was elected to the North Carolina state senate. He was an influential and effective representative for the western part of the state. He served in the legislature from 1849 until the beginning of the Civil War in 1861. Long a states’ rights advocate, and bitter over the federal government’s treatment of native tribes, Thomas was quick to vote for secession in May of 1861. Determined in his Confederate support, he viewed Lincoln as a little more than “a modern-day tyrant.”

Thomas was 56 years old as the Civil War dawned. He had been married less than five years to Sarah Jane Burney, 27 years his junior. Nevertheless, he lobbied the Confederacy to create a Cherokee unit to support the war effort. Granted his wish, Thomas began to organize a local force. Elected captain, by mid-1862 he had mustered a regiment of five companies, three white and two Cherokee. He also formed an additional battalion of two white companies under a separate command. As the local residents were sometimes referred to as “Highlanders,” Thomas’ men soon became known as the “Highland Rangers.” By late 1862, Thomas was in command of a mounted regiment that fluctuated in size from 1,500 to 2,000 men. They were officially designated “1st Regiment, Thomas Legion.” However, what began as a small fighting force of Cherokee led by their aging white chief, would be remembered in history simply as “The Thomas Legion.”

The Thomas Legion spent the majority of the war fighting in East Tennessee and western North Carolina. As the war worsened, Thomas and his men, shrunk to about 500 troops, were ordered to join the Confederate forces defending the Shenandoah Valley. Outnumbered more than two to one, the battle for the Shenandoah was a disaster for the Confederacy. Thousands were killed and many more wounded and taken prisoner. Fewer than 100 members of the Thomas Legion returned to their families in Western North Carolina.

Upon his arrival back in the mountains, Thomas, now 60 years old, began replenishing his company. The Legion grew to 1,200 men of whom 400 were Cherokee. This time they stayed close to home, assuming responsibility for regional protection. As the War neared its end, the Thomas Legion surrounded the Union-occupied town of Waynesville. It was there they learned of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. With dignity and honor, Thomas met with the Union commander, Colonel W.C. Bartlett. A wonderful story tells how Thomas picked and was escorted by “twenty of the biggest Cherokees” he could gather. The Thomas Legion marched into Waynesville and became the last Confederate company to surrender in North Carolina. Bartlett was so impressed by the Confederate leaders and their escort that he allowed them to keep their arms and equipment and return to their homes. Though defeated, Thomas led his men back to the Qualla Boundary with great pride and affection.

Returning home, Thomas encountered a changed world. The strain of active military service had taken its toll on both his physical and mental health. Also, adding additional stress, he was expected to renew his responsibilities as leader of the North Carolina Cherokees. He was pardoned for his Confederate activities by President Andrew Johnson. However, as his mental condition continued to deteriorate, it became difficult for him to function in any of his previous capacities, as family man, merchant, or chief. In 1867 he entered a state institution in Raleigh. Up until his death in 1893, Thomas lived in and out of mental hospitals.

His end was sad, but that does not diminish the impact William Holland Thomas made on western North Carolina and the Cherokee people. For many years he used Cherokee money, as well as his own, to purchase land for the tribe. These purchases make up much of today’s Qualla Boundary within the Cherokee Indian Reservation. Communities like Paint Town, Bird Town, Big Cove, Wolf Town, and Yellow Hill were named by Thomas. He is remembered in the outdoor drama Unto These Hills, and the Thomas Legion battle flag is on display at the Museum of the Cherokee Indian.

Known as Wil Usdi (Little Will) by his beloved Cherokee, William Holland Thomas is a true regional treasure. The stories of his personal life and services during the Civil War are riveting, informative, and an important part of our mountain heritage.

Essay by Timothy N. Osment

History, M.A.

WCU 2008

For more information please see:

- Rebel Chief: The Motley Life of Colonel William Holland Thomas, C.S.A., Paul A. Thompson,

- Confederate Colonel and Cherokee Chief: The Life of William Holland Thompson, Stanley Godbold Jr.,