Mountain Guardian Hugh Morton Receives Mountain

WCU Press Release, 1991

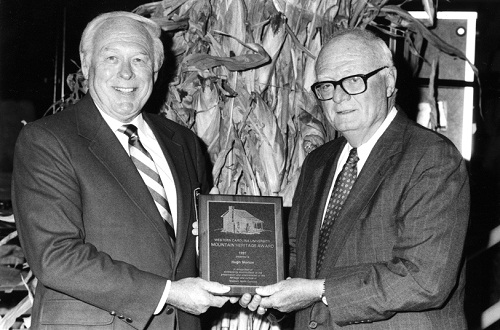

Hugh Morton owner and developer of Grandfather Mountain and a leader in efforts to combat the damaging effects of acid raid, is the 1991 winner of the Western Carolina University Mountain Heritage Award.

The award was given to Morton by WCU Chancellor Myron L. Coulter Saturday, September 28, at the university’s 17th Mountain Heritage Day celebration. It is given annually to individuals or organizations that help to preserve and interpret the history and culture of Western North Carolina.

Morton was chosen for his efforts to preserve the natural heritage of the mountains and “his magnificent legacy of achievements and contributions,” Coulter said. “His slide show on acid rain damage to our spruce fir forests has been seen by thousands of North Carolinians and other U.S. citizens,” and has recently helped to focus “national and international attention on the plight of our mountain top evergreens,” Coulter said. Coulter added that “uncounted numbers of visitors have delighted in the natural habitats and sheer scenic beauty of Grandfather Mountain and those uncounted numbers will view the earth with increasing respect as a result of the direct impact the Grandfather experience has on thinking, and perceptive people.”

Morton’s name is closely linked with his interests in Grandfather Mountain, Mildred the Bear, hang gliding, the Grandfather Mountain Nature Museum, the battle USS North Carolina, the Cape Hatteras lighthouse, the Linn Cove viaduct of the Blue Ridge Parkway, the North Carolina ridge law, the Wilmington Azalea Festival, breathtaking photography, the Highland Games and the Singing on the Mountain festival.

Though a native of the coastal town of Wilmington, it is for his efforts to guard in the state’s mountains that Morton is perhaps best known. He inherited ownership of 5,964-foot Grandfather Mountain, highest in the Blue Ridge Mountains, in 1952 when the estate of his grandfather, Hugh MacRae, was divided among family members. He has steadfastly defended it since, especially against early efforts to route the Blue Ridge Parkway along the mountain’s side.

In 1961, when “the State” magazine named him North Carolinian of the Year, it said “ perhaps he is the only man to hand the powerful U.S. Interior Department three successive and stinging defeats, and he did it after virtually all of his friends advised him to surrender.” Morton has often appeared before Congressional committees, and in countless public and civic arenas in support of preservation causes. For his efforts he has such awards as the National Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Award and the North Carolina Public Service Award.

Morton has been a point man in the battle against acid rain for several years. In a recent challenge to sportsmen, Morton wrote: “What do you do when you are not a scientist, but you know enough about science to realize that three of your favorite game fish – rainbow trout, brown trout, and smallmouth bass – will all be dead before the federal government designation for acidified waters is ascribed to the lakes and streams where the fish were unable to survive? Well, that’s the way the situation is tilted to downplay the effects of air pollution, and it makes me boil.”

“What can an ordinary citizen do? Stay in touch with your US. Senators and congressmen, for they are your only voice. Let them hear that you know the widespread damage air pollution has done in Canada and Eastern Europe, and under no circumstances should they allow this gradual and terrible destruction to happen here.”

Morton once told a Raleigh News and Observer reporter jokingly that he was “just a natural born, rosy-cheeked do-gooder, but I get interested in things and I do what I’m interested in.” It is for his longstanding interest in the natural heritage of the North Carolina Mountains that Morton was chosen for the 1991 Mountain Heritage Award, Coulter said.