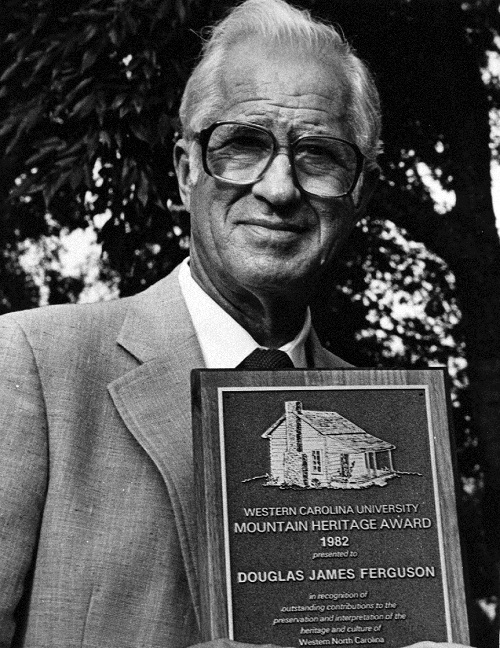

Presentation of 1982 Mountain Heritage Award to Douglas James Ferguson

Western Carolina University’s 1982 Mountain Heritage Award went last Saturday to Douglas James Ferguson, a potter of international reputation and a native of Possum Trot in Yancey County, for “creating works of art that preserve in sculpture, pottery, and tile the life of our mountain land.”

In a citation accompanying the presentation, WCU Vice Chancellor H.F. Robinson, said that Ferguson’s art “forms today a rich part of the culture that will be the heritage of future generations.” The award, presented annually during the celebration of Mountain Heritage Day at Western Carolina University, came as a complete surprise to the 70 year old master craftsman who operates the famed Pigeon Forge Pottery five miles northwest of Gatlinburg across the mountains in Tennessee. With his alma mater, Mars Hill College, meeting the WCU Catamounts on the gridiron for the first time since 1967, Ferguson had been persuaded by his wife, Ruth, to join their daughter, Esther Booth; his sister, Margaret Zelaasko, and cousin, Nelleen Robinson, for the Heritage Day celebration.

A bronze tablet presented by Dooley to Ferguson read: “Western Carolina University Mountain Heritage Award, 1982 presented to Douglas James Ferguson in recognition of his contributions to the preservation and interpretation of the heritage and culture of Western North Carolina.”

In a ceremony on the lawn of the Chancellor’s Residence, Dooley pointed out that “the award is yet young, established only in 1976.” “It has gone to authors, to preservers of mountain folk music and dance, to those who have helped keep alive in unique ways the Indian and pioneer heritages of our region, and to the region’s largest newspaper,” he explained. “This year, it is a special source of pride for the university to recognize a person who is helping to create a very tangible part of our heritage, and to preserve in a singular way many aspects of our broader culture. “This he is doing through a special form of art,” Dooley said, “and he thus becomes the first artist, the first artisan, and the first craftsman to be recognized with the Mountain Heritage Award. “We hope that this particular superlative will be as significant and meaningful to him as it is to the university.

“His 47 years as a craftsman and artist have given us, the Southland, the nation, and many other parts of the world a perspective on life and customs of Southern Appalachia in a unique form, that of ceramics and pottery. “Since 1935, Douglas James Ferguson, whom we honor today with the 1982 Mountain Heritage Award, had developed to a high art, ceramics stoneware, pottery, and artistic tiles, and is making a lasting contribution to our mountain heritage.” Dooley said that Ferguson’s work is imbued not only with technical excellence not only with technical excellence alone we would gladly honor him.”

“Beyond the evident skill of the master craftsman, however, lie artistic qualities of such rare beauty that they can only be described as spiritual,” Booley said. “Thus, he represents an artist at culmination, one who adds to the results of his studies and training, that is, his technical skills, the values and worth of moral and ethical comment upon the world he beholds. “This, then, is the artist we celebrate with this award, for the sheer beauty of his creations provide us all an example of true meaning of the artist.

“Happily,” Dooley continued, “Douglas James Ferguson takes us beyond the joy we find in the technical excellence of his creations, and beyond even that recognition of beauty that provides the thrill we find in genius. “He takes us, even today, to the added recognition that his skill as a craftsman and his worth as an artist are joined in creating works of art that preserve in sculpture, pottery, and tile the life of our mountain land. “What he has known since his earliest days is expressed in his art. From his Pigeon Forge Pottery comes far more than beautifully made wares, for from it and from him come works of art that have been celebrated from Buckingham Palace to the Kingdom of Nepal, and now, too, receives the appreciation of this University. “I take great pride,” Dooley said in conclusion, “in presenting the 1982 Mountain Heritage Award to Douglas James Ferguson, a man whose art forms today a rich part of the culture that will be the heritage of future generations.”

Two of Ferguson’s most stupendous works, both done as gifts to Mars Hill College, where he majored in art, are his Appalachian mural called “Heritage” and a recently completed fountain with water flowing from a wall whose sides are paneled with hand-incised, hand-painted tiles of old time mountain quilt designs fired in a smoky kiln.

Both the fountain, which is really a catalogue of traditional mountain quilt patterns, and the ceramic mural, which depicts the tools and the wooden artifacts our mountain forebears made with them, come directly out of Ferguson’s boyhood experiences on Possum Trot and out of what he calls “my mountain heritage.”

One of his most celebrated pieces is the tea set he made for the State of Tennessee to present as a gift to Queen Elizabeth in 1957. Known as the Clingman Dome Tea Set, named by Ferguson for the highest peak in the Great Smokey’s, he designed it, made it out of his famous red clay, and covered it with special black glazes from a family formula that is considered on of the 10 most beautiful glazes in the world.

In 1980 he designed and built the Scottish memorial cairn at Grandfather Mountain. He has held membership in the Southern Highlands Handicraft Guild longer than any other member, and is known as “one of America’s most successful creative potter-designers.”

A Rotarian with 35 years of perfect attendance, he was honored by Rotary with a certificate of distinguished service for his vocational service. And his Appalachian mural at Mars Hill College brought him a certificate designating him as a Paul Harris school.

Fountain at College Quilt Made of Clay

John Parris “Roaming The Mountains”

Aug. 22 1982

MARS HILL – Douglas Ferguson, a 70-year-old mountain-born potter with a Della Robbia touch, has come up with a creative combination of two traditional mountain arts – clay and quilting. His latest creation is a fountain with water flowing from a wall whose two sides are hand-painted tiles fired in a smoky kiln. Located on the campus of Mars Hill Colege, on sited of the instititions’s first building in 1856, the work is really a catalogue of traditional mountain quilt patterns.

And it complement the ceramic mural by Ferguson on a wall of the administration building that depicts the tools and the wooden artifacts our mountain forebears made with them. The designs of both and the elements which comprise them come directly out of his boyhood esperiences and out of what he calls”my mountain heritage.” For Fergustion was born just up the way on Possum Trot, a small settlement near Bald Creek in Yancey County. He grew up there and attended grammer school and high school at Balf Creek in Yancey County. He enrolled at Mars Hill in the fall of 1931 and completed his studies in the spring of 1933 with a major in art.

In 195 he began working for the Tennessee Valley Authority in its ceramic research laboratory at Norris, Tenn. And in 1946 he and his father-in-law Ernest Wilson founded Pigeon Forge Pottery on the banks of the Little Pigeon River five miles northwest of Gatlinburg. Since then he has become renowned as a potter, artist, and designer, He has been commissioned to create special pieces for such dignitaries as Queen Elizabeth, and he has lectured all over the world.

His mountain heritage is a love he cherishes to himself and champions to the nations. And through much of his he is trying ro preserve it for future generations.

Both the ceramic mural and the fountain with its quilt patterns are symbols of that heritage and both are his gifts not only to the college but to all whose rootholds go deep in mountain soil

In designing the fountain, which he finished a couple days ago, Ferguson said he wanted “tp create a youthful springtime feeling with the use of the Southern Appalachian traditional quilting patterns

“the Six very small water flows on each side of the tiled wall,”he said, “give the fountain a very elegant simplicity without a feeling of effort on the part of man.

The handling of these quilting patterns were perhaps the biggest challenge. I wanted to give a new meaning and feeling to them with out losing the excellent quality they have accomplished.”

The wall is 8 feet high and 20 feet 10 inches ong. Each side is paneled with 280 tiles into which have been fired the various quilt patterns, The tile, 12 inches, are seven rows high and 20 rows across,

From the time he began creating the design for the fountain until he got the last tile fired and in place took Ferguson 18 months.

“It was not a matter of cost nor of time,” he said “I couldn’t afford to have any pressure on me or any deadline, because I was creating right down to the last tile, doing things I had never done before in my life.

“From the beginning the thing was a sort of progression of creativity and the invention of new glazes and new colors.

“As each new design was more exciting. I got to the point where I was doing my very best work, all done by hand and painted on individually. When the piece came out of the kiln I was rewarded with god results.”

He pointed out that his ceramic mural of early tools was structural thing, more modeling, more sculpturak, “whereas this was a creativity.”

“It was taking a beautiful piece of material, cloth material, and trying to say something with color and the treatment of the surface of the clay with natural impurities coming through the glaze,” Ferguson said. “Working so that the colors wouldn’t be too bright or too cheap looking but would have a deep meaning of their own.

“This was a totally new experience. I was using the same clay recipes of the clay that works so well, but all the other materialsm colors and glazes were done especially for the timlesm the quilt patterns.

“The handling of the traditional patterns was a terribly exciting thing on that I had enough leeway with color and texture and then was ising the relief.”

Some of the more than a hunderend quilt patterns he captured on the ceramic tiles include Wild Goose Chase, Turkey Tracks, Double Wedding Ring, Kansas Sunflowerm Grandmother’s Fan, World Without End, Job’s Troubles, Feathered Star, Wandering Foot, Rose of Sharon, Robbing Peter to Pay Paul, Crosses and Losses, Log Cabin Bird of Paradise, and Chips and Whetstone.

“One of the most fascinating things about the traditional quilts is the names fiven to them,” Ferguson said. “since the quilt serfed as an artistic expression of the maker, the name was whatever she chose. She moght use the traditional name or she might name it by whatever she had in mind.

“Usually a name held some personal sentimental meaning. Names often were inspired by famililar objects.

“The old pattern Bear’s Paw that you see on the fountain wall reflects in its name the dangers encountered in frontier living. In more settled communities where bears had moved out the name was changed to Duck Tracks or Duck’s Foot.”

He Pointed out one called Drunkard’s Path.

“It’s one of the 10 most beautiful designs,” he said. “Not because of the name, but because of the simplicity of it.”

The fountain with its tiled wall of (* text cuts off*)

Craftsman Recalls Mountain Life

John Parris Sept. 9, 1982 Asheville Citizens-Time

POSSUM TROT- Douglas Ferguson, who is known throughout the world for his ceramic creations, grew up here on Possum Trot in the hills of Yancey County at a time when folks still lived mostly off the land.

Now and then he takes a day off from his Pigeon Forge Pottery over in Tennessee to journey back to the old home place and wander through the now-vacant house where he was born 70 years ago and visit the old bard of hand-hewn chestnut logs where he learned to milk a cow.

A lot of his ceramic work, such as his Appalachian mural just a piece down the road at Mars Hill College, has come directly out of his boyhood experiences and what he calls “my mountain heritage.”

“When I came along,” he said the other day, “our farmstead with its q80 acres, was surrounded by wild locust, sourwood, oak, tulip poplar, chestnut, and pine bordered with thickets of laurel and rhododendron.

“We had a lot of chestnut trees on the place. Our hogs, which ran wild, fed on them, and so did the turkeys, as a boy I picked up bushels of them and sold them down at the store at Bald Creek and in Asheville.

“My boyhood days were terribly important to me. Everything that is depicted in the Appalachian mural I did is an artifact I grew up with here on Possum Trot.

“I used a wooden piggin to hold the milk when I milked the cow. I helped my mother churn the butter in a yellow poplar handmade churn. The butter was pressed in a wooden one-pound mold that had a sweet birch-leaf design. We sold all our surplus butter at the country store.

“I used oak-split baskets for gathering apples, digging potatoes, berry picking, gathering wood chips for starting fire and many other daily chores. “We cut sledded in our own firewood, in winter we kept the hearth fire, back of the large sturdy hand wrought andirons, going just about all the time. It was our only heat beside the fire in the cook stove.

“We kept geese and picked the feather for featherbeds and pillows. We didn’t kill any to eat. They were too valuable and necessary for their feathers.

“I slept on a goose-feather ticking make from the feathers I plucked from the flock of 10 to 12 large geese until I went away to school when I was 18 years old. And I continued to sleep on it whenever I returned home for the summer or a visit.

“Covering me were handmade comforters and quilts, stuffed with wool sheared from our own flock of about 60 sheep.

“My mother had a loom and a spinning wheel. She wove coverlets when I was quite small. She knitted all our long sock and mittens and heavy woolen sweaters dyed a beautiful blue-black.

“My mother was an expert seamstress. She made all my shirts and all the children’s clothes. I didn’t have a store-bought shirt until I went away to school when I was 18 years old, because Mother could make shirt better than the ones you could buy. She made them out of the best broadcloth that could be had.

Our field crops were corn, oats, rye, potatoes, and hay for winter feed. We grew sorghum cane and made molasses. We also grew broom-cord from which we made brooms.

“Back then there was some old timers around here that could use the adze and broad axe with amazing skill. I have used the broad axe to make one horse sled from locust trees.

“The reaping hook was not used much during my childhood but was sometimes used to cut grains that had fallen on the ground or to cut selected grains for seed. The grain cradle was used to cut oats, rye, and wheat.

“Now, the hillside plow was one of the most useful of farm tools. I was 16 years old and weighed about 135 pounds when I first used the plow on a steep hillside. It was some experience.

“Our very large yellow poplar oxen yoke was last used in 1922 on a big pair of oxen pulling logs to a sawmill.

“We had a team of horses, too. I remember our farm wagon well. I learned how to grease the axles, and when the metal tire become too loose in dry weather, my job was to soak the wheel in the creek to make the wood expand, thus making the tire tight.

“I learn early how to rive boards and became quite good with a froe and mallet. I was 12 years old and helped rive the boards when we had to put a new roof on the barn.

“And I got pretty good with the drawknife. I used it to taper the sides of shingles, to fashion axe handles, and to make legs for stools.

“Religion played a large part in mountain consciousness. I attended a Baptist meeting-house, a large one room building in the evening the room was lighted by a kerosene lamp on the organ and another on the pulpit. We sat on plank benches.

“Back then educational requirements or special denominational training for the preacher in the old-fashioned mountain churches were negligible.

“Singing conventions offered each church a chance to show off its choir usually recruited from the congregation. Using hymnals with shape notes, the choirs sang in competition without organ accompaniment, their choir leaders launching them into hymns with tuning fork.

“Afterwards, relatives and visitors from other parishes were invited to help themselves to the platters of fried chicken and roast meat, cold sweet potatoes, home-canned peaches, and stacked pies.

“Thus the people came together for their social events.”

He paused a moment, let his eyes run across the backyard to the smoke house and beyond to the spring.

“I consider myself very fortunate to have had these experiences,” he said. “For me they contributed to a sympathetic understanding of our past.”

Mountain Heritage Day Award Announced

The Cashiers Chronicle

Sept. 22, 1982

During the Mountain Heritage Day activities, Douglas James Ferguson of Possum Trot in Yancey County was presented the eighth annual Mountain Heritage Award for his contributions to the preservation of the history and culture of Southern Appalachia. Ferguson, widely recognized as a potter and sculptor, is the first artist to win the annual award presented by Western Carolina University.