Creative Commons Image Obtained Through Flickr

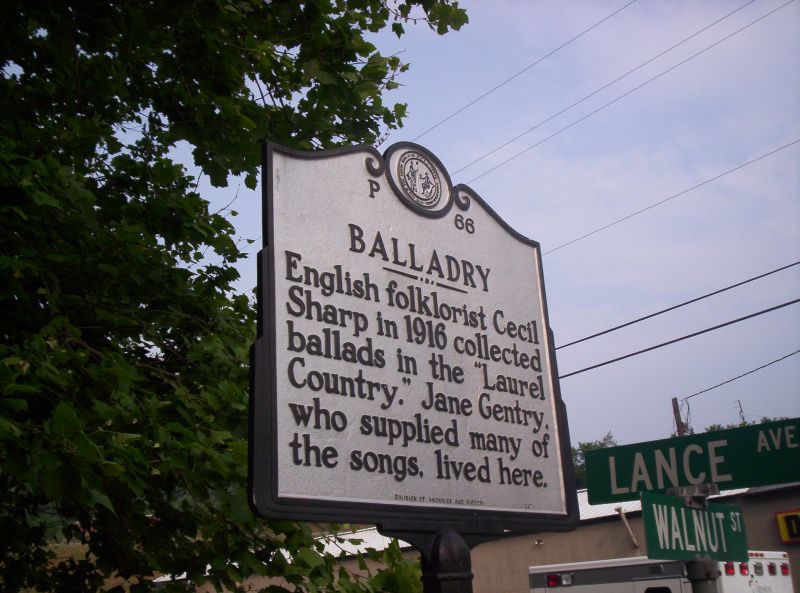

In 1915 Cecil Sharp, an important collector of traditional English ballads, was informed that many Appalachian singers were singing old English songs. Between 1916 and 1918 he toured western North Carolina and other Appalachian states, recording over 500 ballads with English roots. His most valuable source was Jane Hicks Gentry from Hot Springs, North Carolina. Gentry was a member of North Carolina’s renowned storytelling and singing family, the Harmons. She shared over 70 of her songs with Sharp. In 1917 Sharp published his collection of songs in a book entitled English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians. The book is the most important source of traditional Appalachian songs. In 2000, the movie Songcatcher portrayed Sharp’s experience collecting ballads in Appalachia.

Audio Moment

Cecil Sharp

Cecil Sharp

Traditional Songs, like Traditional Foods, represent more than initially meet the eye. They represent family ties, a sense of place, community, and shared joys & despairs. Simply, they represent history. Not surprisingly, this is exactly what English Folklorist Cecil Sharp discovered (and confirmed) as he toured Southern Appalachia in the early 20th Century.

Cecil Sharp was born in London in 1859. As a young man he studied at Cambridge and went on to teach in both England and Australia. Around 1900 he turned his attention to folk music, traveling the English countryside, documenting and recording the disappearing traditional ballads that only existed in the minds, hearts, and voices of aging generations.

Fortunately (and somewhat reluctantly), Sharp eventually directed his passion for song collecting towards the United States. His initial expectations were low. How could a young, upstart of a nation offer any significant contributions to the study of traditional European ballads? Sharp felt few individuals under the age of 70 possessed the authentic, first person memories and sentiments necessary to truly represent the heritage of fading, passed-down culture. Certainly a bustling, growing United States, full of emerging nationalism and capitalism, with little notice downplayed rather than celebrated the homespun ways of its parents and grandparents. To his delight, and to our benefit, what Sharp found surprised and awed everyone.

On three separate trips to America, between 1916 and 1918, Cecil Sharp spent 46 weeks in remote Southern Appalachian communities. He collected almost 2,000 songs & arrangements. Some were of obvious English origin; others – like the square dance – were distinctly American. Undoubtedly Sharp’s most valuable stateside association was with Olive Dame Campbell, wife of educator, social activist, and preservationist, John C. Campbell.

Long before Sharp and Campbell met, Olive Dame had spent years accompanying her husband on his journeys surveying the school systems in rural Appalachia. During these trips, Campbell was first exposed to mountain songs and ballads. She wrote of one such experience, at the Hindman Settlement School in Kentucky in 1907 – and its profound influence on her life,

“Shall I ever forget it. The blazing fire, the young girl on her low stool before it, the soft strange strumming of the banjo – different from anything I had heard before – and then the song. I had been used to singing Barbara Allen as a child, but how far from that gentle tune was this – so strange, so remote, so thrilling. I was lost almost from the first note, and the pleasant room faded from sight; the singer only a voice. I saw again the long road over which we had come, the dark hills, the rocky streams bordered by tall hemlocks and hollies, the lonely cabins distinguishable at night only by the firelight flaring from their chimneys. Then these, too, faded, and I seemed to be borne along into a still more dim and distant past, of which I myself was a part.”

In 1916, Cecil Sharp with his secretary and assistant, Maud Karpeles, arrived in America – where he initially conducted a series of lectures on English folk music and its influence on community. Throughout, Sharp was not silent of his forgone conclusion that there was no such thing as American folk music. By the time he reached Chicago, he feared his trip would yield few fruits within his field of research. Soon after, arriving in Asheville NC, Sharp called upon Olive Dame Campbell, who he had met briefly in England a year earlier. To Sharp, Campbell insisted that the inhabitants of the Southern Appalachians were still singing the traditional songs and ballads which their English and Scottish ancestors had brought out with them at the time of their emigration. And she set out to demonstrate just that.

Under Campbell’s direction, and often company, Sharp ventured into the remote communities of the region. His discoveries were extraordinary. He recorded dozens of diary entries … In Madison County, NC, Sharp crossed the French Broad on a punt to access the county seat of Marshall and nearby town of Hot Springs. The ferryman told Sharp about his wife’s singing (whom Sharp met) and that “whilst in Hot Springs he could take down a good song from the postman” “… who [subsequently] told him to look up a blind girl named Linnie Landers and get some good songs from her.”

In England, Sharp was accustomed to collecting songs from elderly people – in America he was often surprised by the young age of his singers. He writes, “Floyd Chandler sang Mathy Groves very beautifully and he is but 15. Another singer, David Norton, was seventeen years old. Addie Crane was twenty-one, and Linnie Landers only twenty years old. Even the redoubtable Mrs. Gentry was only in her fifties!”

To his collection, this initial trip to America provided Sharp over 400 songs and dances, and served to stimulate both his interest and desire to return as soon as possible. Campbell suggested an autumn visit as a good time to collect ballads as the mountain residents would be involved in “frolics, log rollings, corn huskings, ‘lasses bilings, watermelon cuts, and so on.” She added, however, that these events “may be accompanied by excessive drinking and even less desirable features.”

When Sharp returned in 1917, one particularly frustrating venture was along the railway that ran out of Asheville to & through the westernmost counties of North Carolina. He writes of the trip, “Balsam is on the highest point on the Asheville – Murphy line, and is 3550 feet up. The weather however is as hot as it can be and we have found our long tramps over the mountains rather fatiguing – all the more so because so far we have hit on no singers to speak of. The fact is we are too close to Waynesville – a large industrial centre, and the inhabitants have been partially spoiled, that is from my point of view. The log cabins are primitive enough but their owners are clean, neat and tidy, looking rather like maid-servants in respectable suburban families. It is sad that cleanliness and good music, or good taste in music rarely go together. Dirt and good music are the usual bed-fellows.”

The taint of “progress” reflects just a hint of the many harsh realities of Sharp’s American treks. Though his collections grew, so did his professional and personal challenges. Financial ruin was always lurking, forcing him on occasion to give up collecting and return to the lecture circuit to secure funding & support. Sharp’s family struggled as well – often wondering when and the condition of his return. On one particularly long absence, Sharp’s wife suffered a stroke while he was away, requiring his abrupt departure and subsequent delay in returning. In addition, Sharp was not a hearty man and his health, like his travels, followed a seemingly endless series of peaks and valleys. Writing of an especially grueling excursion in Kentucky, “…greatly disappointed in Harlan. It is a dirty, noisy, vulgar mining town. Hotel impossible. Very depressed.” Notably though, it was to be one of the most productive periods in Sharp’s collecting – adding almost 200 songs to his collection. However, poor health once again emerged, “’Feel very ill on waking. Temperature still up. Feel very depressed – Feeling very ill and hopeless.” Here his assistant writes, “Cecil not at all well … got a mattress (and) slept on floor in his room.” Adding to his discomfort, Sharp began to suffer from violent toothaches, prompting doctors to extract all of his teeth.

Despite the grueling nature of his three-year project, Cecil Sharp’s efforts had an immediate effect on American folklore, entertainment, and academics. His tales & findings influenced an entire of generation of social historians, encouraging them to become more active in researching their own folk cultures. Within a decade, modern country music was borne of traditional ballad recordings produced in the heart of Southern Appalachia. Within “History” courses, universities included a nod to “Heritage”. However, more relevant, was the neighborhood impact. Music festivals, performances, and competitions began appearing nationally and throughout the region. Asheville’s Mountain Dance and Folk Festival, first held in the 1920s, is a an example of a community taking what Sharp “discovered” and weaving it into the fabric of their daily lives – despite the onslaught of progress and the modern age.

So, the next time you hear a mountain waltz, it is likely the haunting tune in the background is one of the many Cecil Sharp encountered in the backwoods of a young United States. The music at the next square dance you attend certainly grew of European roots replanted by a displaced people. Few characteristics of a culture tell a story in the way does a song. This fact, without question, is what Cecil Sharp provided to himself, America, and indeed, the world. Music is certainly one of the ties that bind together our mountain heritage.

Note: For an interesting and revealing glimpse into the interactions between the traditional mountain musicians of the early 20th century and the “outside” musicologists who sought them, view the 2000 movie, “Songcatcher”.

Sources

- C.H. Farnsworth and Cecil Sharp, editors Folk-songs, Chanteys and Singing Games.

- Maud Karpeles. Cecil Sharp; His Life and Work

- Maud Karpeles, editor, The Crystal Spring: English Folk Songs collected by Cecil Sharp.

- A.H. Fox Strangways, Cecil Sharp.

- C.E.M. Yates, Dear Companion: Appalachian Traditional Songs and Singers from the Cecil Sharp Collection.

- http://www.themorrisring.org/more/cs.html

- http://www.mustrad.org.uk/articles/sharp.htm

- http://www.answers.com/topic/cecil-sharp

- http://www.traditionalmusic.co.uk/english-folk-songs/