Shape notes were invented in the late 18th century to simplify teaching people to sight-read unaccompanied sacred musical scores. They were called shape notes because, instead of drawing all of the music scale’s seven notes with round shapes, each note was represented by either a triangle, square, oval, or diamond shape, called fa, sol, la, or mi, depending on its position in the scale. Singers usually perform in four-part harmony — alto, tenor, treble, and bass — unaccompanied by instruments. Shape note singing has enjoyed wide popularity in Appalachia. Dozens of hymn books have been produced, with the most popular called The Sacred Harp. All-day singings, accompanied by covered dish meals, are held on church grounds. They are most often scheduled outdoors in the summertime.

Audio Moment

Shape Notes

Shape notes

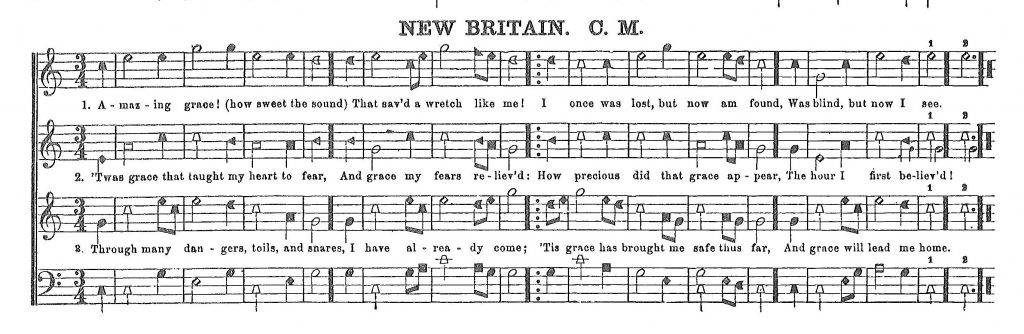

Before describing the fascinating history and heritage of Shape Notes, it is helpful to understand just what they are and how they work. Think of Shape Note music as a combination of three components. After singers identify the key of the piece, they perform it by linking together the notes on the musical scale, the shapes of the provided notes, and then the syllables (or words) of the song. It is not necessary to read music in a traditional sense to determine the tune of an arrangement.

There are four syllables used before Shape Note singers substitute the actual words of a song: Fa-So-La-Ti. Later, three more syllables were added to the original four: Do-Re-Mi. Together they produced the familiar Do-Re-Mi-Fa-So-La-Ti. “Do” was eventually added to the end of the scale to provide a full, eight-note octave. Do-Re-Mi-Fa-So-La-Ti-Do. Purists embrace the original four syllables and their corresponding shapes: a triangle (Fa), an oval (So), a square (La), and a diamond (Ti). Shape Note singers perform by combining these simple shapes (notes), their position on the musical scale, and the provided words of a song.

Canton, North Carolina’s Liz Smathers-Shaw notes, “The beauty of reading shaped notes is that you need only look for the shape of the note rather than the lines where the note is placed. And when you read the ‘Do’, that’s the key the song is in. … It teaches you a quick way of getting into the music.”

Upon first glance, Shape Note singing may seem somewhat cumbersome and complicated but its origins were inspired by simplicity, mass appeal, and participation. Certainly, the naming of notes as an aid to sight reading music has been around for hundreds of years. However, its modern history and development, primarily in the Appalachian regions of the United States, is truly unique. When early European settlers and their descendants spread through the early American frontier written music and fine instruments were a scarce, rare luxury.

In order to increase musical literacy (and make money) two early American publications appeared that featured music using shape note heads, The Easy Instructor (1801) and The Musical Primer (1803). Shape Notes proved popular and soon a wide variety of hymnbooks were produced making use of them. Eventually, a “better-music movement” took hold in the Northeast and the Shape Notes format was deemed uncivilized. Consequently, in “civilized” circles, music returned to its traditional formality. However, in the South, and especially in Appalachia, Shape Notes became entrenched and multiplied into a variety of traditions, called upon to supply entertainment, socialization, and most notably, religious worship.

One early conduit for Shape Note singing, the Singing School, was originally a vibrant social institution in Great Britain. It took hold in colonial America and soon traveling singing-school masters would set up in communities for three and four week periods, teaching both secular and sacred music to citizens anxious for a diversion. When the better-music movement swept the North, Singing Schools faded there, but they soon found a welcoming, permanent home in the South. In this region, the combination of the English singing school, early Shape Notes, and an oral, Celtic, folk-tune heritage joined an awakened religious fervor to produce the musical associations now identified with Appalachia and an independent, agrarian, sustenance way of life.

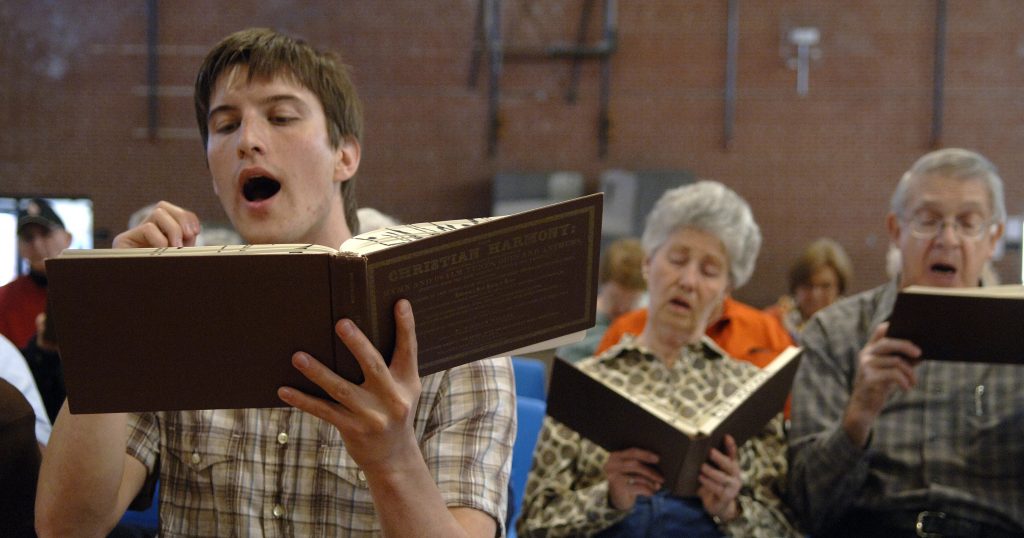

The Singing School sessions soon transitioned into “singing conventions” where folks would bring their “harps and harmonies” and gather to sing for hours or days at a time. These “socials”, usually held in the down time between planting and harvest, grew to include potlucks, preaching, and local talent competitions. It was also an opportunity for young folks to meet members of the opposite sex. Even today, many older southerners associate these gatherings with their courting days. It is no surprise that as time passed, the Shape Note system these singings followed became firmly entrenched in the hearts and traditional practices of the isolated communities of the Appalachian region.

More often than not, the Shape Note system was used with traditional and folk hymns. In fact, traditional arrangements of Christian hymns like Amazing Grace were soon replaced by Shape Note compositions – usually eliminating any musical accompaniment. This tendency towards an emphasis on solo and group singing became known as “Sacred Harp” – referring to the human voice, the instrument all people are given, by God, at birth. Shape Note and Sacred Harp performances stressed glory and heavenly rewards. Soon, dozens of religious songbooks appeared and publishers sent polished quartets out to perform Sacred Harp – and to sell books.

Kentucky Harmony is generally considered the first Southern Shape Note songbook. It, and many others, introduced what eventually became “folk hymns” where melodies plucked from the oral tradition were harmonized in a native idiom and set to sacred words. These hymns, including classics like Amazing Grace and How Firm a Foundation were standard revival songs and sung at camp meetings throughout rural Appalachia and the surrounding foothills. Eventually, an increased frequency of secular music began to appear in subsequent songbooks. Organizations like the Southern Musical Association (1845) and the Chattahoochie Musical Association (1852, still active) were established. Here teachers met to compare and develop additional arrangements, and to demonstrate the accomplishments of their efforts through live performances. – all still in accord with traditional Shape Note practices. However, the secular segment of the practice began to fade (as popular trends and fashions do) and as a result the sacred aspect of the music emerged as the dominant preserver of the Shape Note and Sacred Harp.

Today, Shape Note singing and Sacred Harp, though not widespread, thrive in small community pockets throughout Appalachia – and have experienced a resurgence outside the region. Shape Note adherents follow the sacred culture of worship passed down through the generations. Gavin Campbell of the University of North Carolina notes, “Shape-note singing provides participants with an important artistic, social, and religious framework within which to understand their relationship to one another and to God.” Old-timer Quay Smathers, born in the Dutch Cove community in 1913 just west of Asheville, is a good example of the lasting legacy of Shape Note singing. Observers noted that Smathers, “more than anything, imparted a warmth in his music, as if each note came with a flickering tongue of the Holy Spirit, as if he were the shepherd welcoming anyone and everyone through the heavenly gates into the paradise of church songs.”

It is essential we both honor and appreciate the gifts that these preservers of culture provide. Their simple, sincere form of religious praise is a valuable means of transmitting musical knowledge, skills, and traditions to future generations. The history they represent threads through our region and those who reside here. An important part of our heritage can be found in the true harmonies of the human voice, often residing just up the hollow in the little, clapboard church protected by a small, straight steeple and an immense, blue sky – the heritage that is Shape Note singing and Sacred Harp.

Sources

- The Encyclopedia of Southern Culture

- The Encyclopedia of Appalachia

- A Sacred Feast: Reflections on Sacred Harp Singing and Dinner on the Ground by Kathryn Eastburn

- Music in the United States by H. Wiley Hitchcock

- White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands by George Pullen Jackson

- The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and its Music by Buell Cobb

- “What are the Shapes and Why?” in Prairie Harmony, Volume 2, #1, 1991 by Keith Willard

- “‘Old Can Be Used Instead of New’: Shape-Note Singing and the Crisis of Modernity in the New South, 1880-1920.” in the Journal of American Folklore 110, 1997 by Gavin James Campbell

- http://mountaingrownmusic.org/quay-smathers.html

- http://www.arts.state.ms.us/crossroads/music/sacred_harp/mu4_text.html

- http://www.paperlesshymnal.com/shapnote/shaped.htm

- http://fasola.org/

- http://fasola.org/introduction/note_shapes.html

- http://web.mit.edu/user/i/j/ijs/www/shapenote.html

- http://mountaingrownmusic.org/shape-notes.html

- http://www.mit.edu:8001/people/ijs/sn/sn-hist.html

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shape_note

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_Harp